Scubapro’s Pilot Regulator, how it came to be.

Mar 2, 2019 22:32:49 GMT -8

luis, nikeajax, and 5 more like this

Post by rtonyc on Mar 2, 2019 22:32:49 GMT -8

Scubapro’s Pilot Regulator, how it came to be.

There is a rumor that the Scubapro Pilot Regulator was created by a MIT student for a class project. NOT TRUE. I invented the Scubapro Pilot (US Patents 4,076,041 and 4,029,120 and D245,121). Now in my late 70’s, it is time for the true story of the Pilot Regulator be disclosed and history corrected.

The first photo shows a production Pilot partially cutaway to reveal the interior, my hand built prototype is in the middle, along with a white-cover pre-production first article. The next photos show other views of one of the prototypes. Note that the prototype does not have a dive-predive switch but it has a knurled ring above the mouthpiece which by turning enables the diver to adjust the venturi effect on the fly.

The prototypes were hand built in my home workshop completely independent of Scubapro. I was 35 at the time. No I was not a student. In 1972 (three years before completing Pilot) I received a Ph.D. degree in Engineering from the University of California in Los Angeles and subsequently specialized in designing scuba diving equipment (and mountain climbing equipment, but that is another story). The Pilot was offered to USDivers, Techna and Scubapro. Scubapro was eventually granted an exclusive worldwide license to manufacture and market the invention. I retained full ownership of the Pilot patents and received royalties from Scubapro based on sales.

The Pilot was the end result of many iterations developed over a 2 year period. An instrumented breathing machine and pressure chamber were used to evaluate the various Pilot iterations along with extensive underwater testing . A license for Pilot was offered only after the design was thoroughly proven.

The next photo shows another Pilot prototype, this one with a single inlet and no venturi adjustment. This is the photo sent USDivers, Techna and Scubapro along with a description of the new regulator to solicit their interest. All three companies responded very quickly.

The suction of a diver’s inhalation moves the regulator’s diaphragm which is mechanically linked to open a spring-loaded valve. Exhaling moves the diaphragm back which closes the valve. A pilot regulator uses a very small valve (the pilot valve) to pneumatically control the opening and closing of a much larger main valve. The inhalation effort to open and close the small pilot valve is significantly less than that required to open and close a large valve. Consequently breathing is significantly easier with a pilot regulator than with a non-pilot regulator. Modern non-pilot regulators use the venturi effect of flowing air through the mouthpiece to boost the suction moving the diaphragm, but even better, a pilot regulator really shines when initiating a breath because at the very start of a breath there is no flow to generate the venturi effect. Furthermore the venture effect changes with depth whereas the ease of pilot valve operation is nearly independent of depth.

The hand-built prototypes worked beautifully, but some of the parts required precise machining. Scubapro followed dimensions exactly as designed, but the then state-of-the-art quality of reasonably priced manufactured parts caused production Pilot regulators to be somewhat temperamental. A good Pilot was a pleasure, but occasionally they were troublesome. In a way the Pilot was ahead of its time, what can be easily machined precisely without excessive cost using CNC (computer numerical control) technology today was not available or practical in the 1970’s.

The prototypes featured a housing made of plated brass which was common for scuba regulators in the 70’s. For the Pilot, Scubapro copied the housing design of the prototypes. Scubapro’s engineers soon decided to design an equivalent plastic housing. The Air 1 plastic housing was originally designed to hold the Pilot mechanism. Along with developing a new housing, Scubapro engineering also designed an alternate, non-pilot mechanism (the Air 1 mechanism) which did not infringe on my patents. Several years of Pilot sales did not meet expectations and the Air 1 mechanism proved to be easier and cheaper to manufacture, so when the Air 1 mechanism was ready for production Scubapro terminated the License Agreement for Pilot.

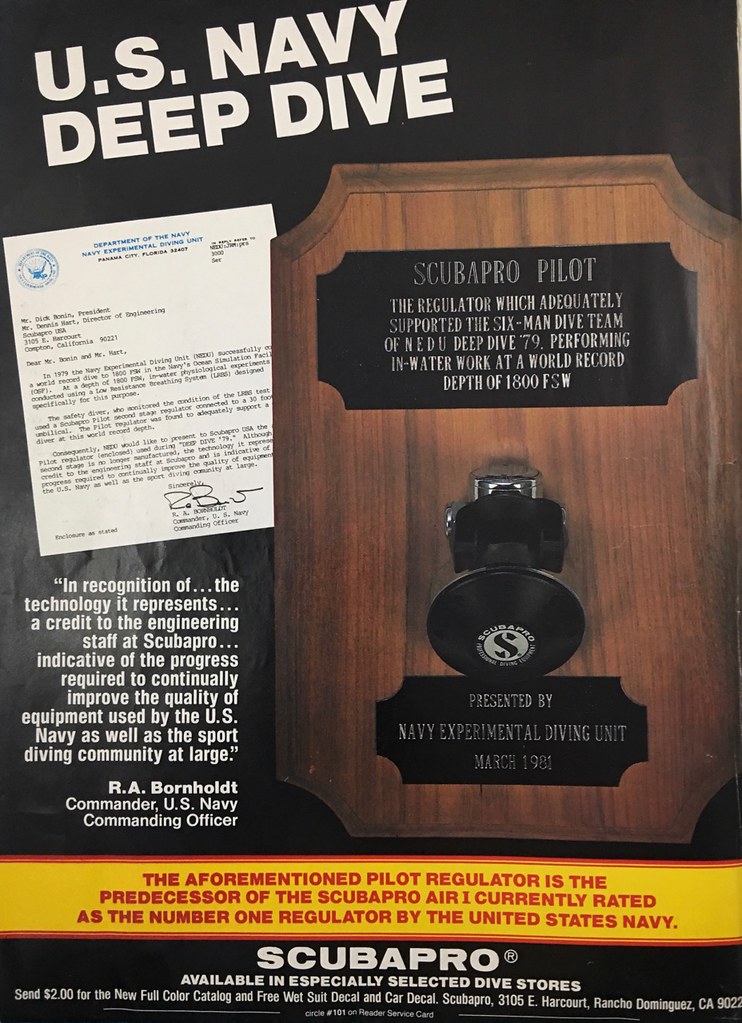

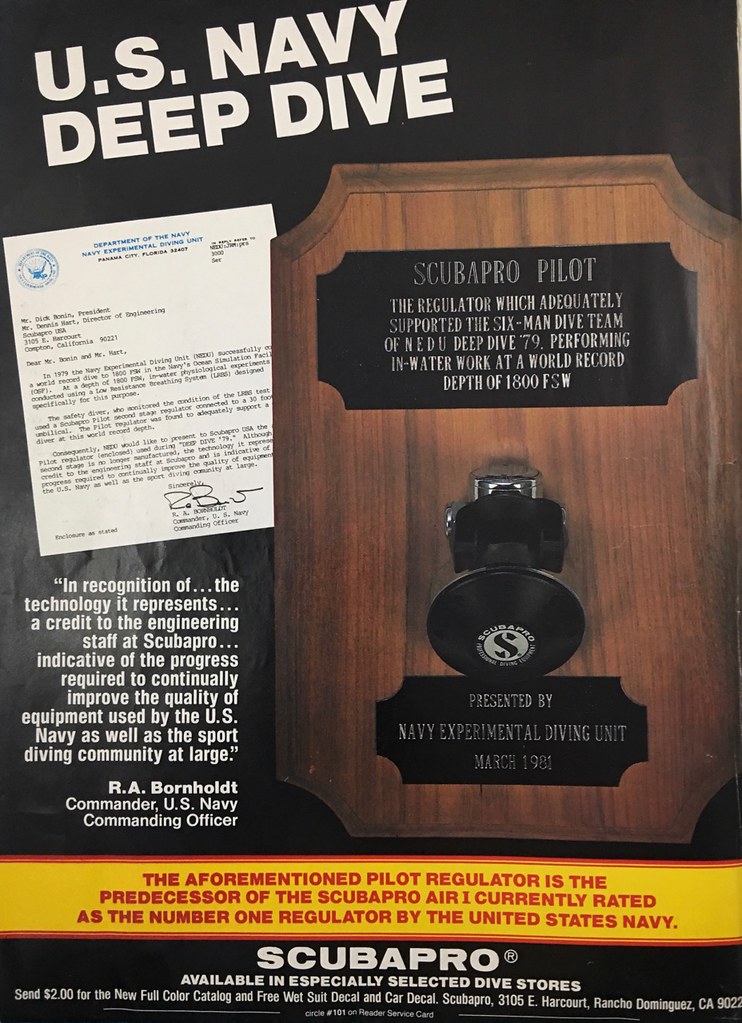

Meanwhile the US Navy Experimental Diving Unit (EDU) was testing the Pilot and determined it to be the most suitable regulator for use during extreme deep dives. As a result of successful deep dives using Pilot, the Navy EDU awarded a plaque to commemorate the design, but that award arrived several weeks after Scubapro had terminated the license. (This plaque was, and possibly still is, displayed at Scubapro USA in El Cajon California). Scubapro had this sensational endorsement from the US Navy for a product they had forfeited the exclusive rights to market. Even so, Scubapro advertised the Navy’s endorsement implying that the non-pilot Air 1 was as good a breather as the Pilot.

Questions have been posted regarding Pilot Regulators that have white or blue covers. Are these regulators somehow special? Actually they are not. I have no idea how many white or blue covers were molded but these covers were fabricated using materials on hand to test the tooling. These samples should have remained with engineering, but apparently some escaped. A serialized Pilot with a white or blue cover is simply a production regulator that someone put a colored cover on.

A Pilot Regulator with no serial number is a true first article pre-production sample. See the photo. The serialized housing on the left is production, the other is pre-production. A non-serialized pre-production Pilot is a very, very rare item.

A few words about early Scubapro from an engineer’s standpoint. Gustav Dalla Valle and Dick Bonin pulled it all together, but without the creative engineering genius of Bob Roberts, David Denis (Gustav’s then brother-in-law), and Dick Anderson, Scubapro would not have produced the cutting edge diving equipment that enabled early Scubapro to succeed and eventually become the diving equipment giant it is today. Scubapro engineering during the early days was very informal. Dave Denis, myself, Bob Roberts and often Dick Anderson would get together once a week and talk diving products over dinner, and into the night. Suggestions and concepts would be traded back and forth and products developed. Bob Roberts was a full time employee of Scubapro and was the mastermind who ran manufacturing and production. Dave Denis, myself and Dick Anderison were actually part-time engineering consultants. Of course there were many others involved behind the scenes in marketing, service and repair, assembly and engineering.

Without a doubt the dominant figure and driving force was Gustav Dalla Valle. I first crossed paths with Gustav when I was in high school. I was a summer hire. The little assembly company I worked for was located in the back room of a machine shop. The company was assembling Scuba Star regulators for Healthways. Gustav was in charge. Everyone went on alert when he walked into production, usually with a glass of wine in one hand and crackers in the other. He had an uncanny ability to walk up to an assembly line, pick a product at random and find something wrong with it. Then all hell would break loose. Perfection and quality were number one. That summer job ignited my desire to design diving equipment. Many years and 3 engineering degrees later I started work as an engineering consultant at Scubapro.

There is a rumor that the Scubapro Pilot Regulator was created by a MIT student for a class project. NOT TRUE. I invented the Scubapro Pilot (US Patents 4,076,041 and 4,029,120 and D245,121). Now in my late 70’s, it is time for the true story of the Pilot Regulator be disclosed and history corrected.

The first photo shows a production Pilot partially cutaway to reveal the interior, my hand built prototype is in the middle, along with a white-cover pre-production first article. The next photos show other views of one of the prototypes. Note that the prototype does not have a dive-predive switch but it has a knurled ring above the mouthpiece which by turning enables the diver to adjust the venturi effect on the fly.

The prototypes were hand built in my home workshop completely independent of Scubapro. I was 35 at the time. No I was not a student. In 1972 (three years before completing Pilot) I received a Ph.D. degree in Engineering from the University of California in Los Angeles and subsequently specialized in designing scuba diving equipment (and mountain climbing equipment, but that is another story). The Pilot was offered to USDivers, Techna and Scubapro. Scubapro was eventually granted an exclusive worldwide license to manufacture and market the invention. I retained full ownership of the Pilot patents and received royalties from Scubapro based on sales.

The Pilot was the end result of many iterations developed over a 2 year period. An instrumented breathing machine and pressure chamber were used to evaluate the various Pilot iterations along with extensive underwater testing . A license for Pilot was offered only after the design was thoroughly proven.

The next photo shows another Pilot prototype, this one with a single inlet and no venturi adjustment. This is the photo sent USDivers, Techna and Scubapro along with a description of the new regulator to solicit their interest. All three companies responded very quickly.

The suction of a diver’s inhalation moves the regulator’s diaphragm which is mechanically linked to open a spring-loaded valve. Exhaling moves the diaphragm back which closes the valve. A pilot regulator uses a very small valve (the pilot valve) to pneumatically control the opening and closing of a much larger main valve. The inhalation effort to open and close the small pilot valve is significantly less than that required to open and close a large valve. Consequently breathing is significantly easier with a pilot regulator than with a non-pilot regulator. Modern non-pilot regulators use the venturi effect of flowing air through the mouthpiece to boost the suction moving the diaphragm, but even better, a pilot regulator really shines when initiating a breath because at the very start of a breath there is no flow to generate the venturi effect. Furthermore the venture effect changes with depth whereas the ease of pilot valve operation is nearly independent of depth.

The hand-built prototypes worked beautifully, but some of the parts required precise machining. Scubapro followed dimensions exactly as designed, but the then state-of-the-art quality of reasonably priced manufactured parts caused production Pilot regulators to be somewhat temperamental. A good Pilot was a pleasure, but occasionally they were troublesome. In a way the Pilot was ahead of its time, what can be easily machined precisely without excessive cost using CNC (computer numerical control) technology today was not available or practical in the 1970’s.

The prototypes featured a housing made of plated brass which was common for scuba regulators in the 70’s. For the Pilot, Scubapro copied the housing design of the prototypes. Scubapro’s engineers soon decided to design an equivalent plastic housing. The Air 1 plastic housing was originally designed to hold the Pilot mechanism. Along with developing a new housing, Scubapro engineering also designed an alternate, non-pilot mechanism (the Air 1 mechanism) which did not infringe on my patents. Several years of Pilot sales did not meet expectations and the Air 1 mechanism proved to be easier and cheaper to manufacture, so when the Air 1 mechanism was ready for production Scubapro terminated the License Agreement for Pilot.

Meanwhile the US Navy Experimental Diving Unit (EDU) was testing the Pilot and determined it to be the most suitable regulator for use during extreme deep dives. As a result of successful deep dives using Pilot, the Navy EDU awarded a plaque to commemorate the design, but that award arrived several weeks after Scubapro had terminated the license. (This plaque was, and possibly still is, displayed at Scubapro USA in El Cajon California). Scubapro had this sensational endorsement from the US Navy for a product they had forfeited the exclusive rights to market. Even so, Scubapro advertised the Navy’s endorsement implying that the non-pilot Air 1 was as good a breather as the Pilot.

Questions have been posted regarding Pilot Regulators that have white or blue covers. Are these regulators somehow special? Actually they are not. I have no idea how many white or blue covers were molded but these covers were fabricated using materials on hand to test the tooling. These samples should have remained with engineering, but apparently some escaped. A serialized Pilot with a white or blue cover is simply a production regulator that someone put a colored cover on.

A Pilot Regulator with no serial number is a true first article pre-production sample. See the photo. The serialized housing on the left is production, the other is pre-production. A non-serialized pre-production Pilot is a very, very rare item.

A few words about early Scubapro from an engineer’s standpoint. Gustav Dalla Valle and Dick Bonin pulled it all together, but without the creative engineering genius of Bob Roberts, David Denis (Gustav’s then brother-in-law), and Dick Anderson, Scubapro would not have produced the cutting edge diving equipment that enabled early Scubapro to succeed and eventually become the diving equipment giant it is today. Scubapro engineering during the early days was very informal. Dave Denis, myself, Bob Roberts and often Dick Anderson would get together once a week and talk diving products over dinner, and into the night. Suggestions and concepts would be traded back and forth and products developed. Bob Roberts was a full time employee of Scubapro and was the mastermind who ran manufacturing and production. Dave Denis, myself and Dick Anderison were actually part-time engineering consultants. Of course there were many others involved behind the scenes in marketing, service and repair, assembly and engineering.

Without a doubt the dominant figure and driving force was Gustav Dalla Valle. I first crossed paths with Gustav when I was in high school. I was a summer hire. The little assembly company I worked for was located in the back room of a machine shop. The company was assembling Scuba Star regulators for Healthways. Gustav was in charge. Everyone went on alert when he walked into production, usually with a glass of wine in one hand and crackers in the other. He had an uncanny ability to walk up to an assembly line, pick a product at random and find something wrong with it. Then all hell would break loose. Perfection and quality were number one. That summer job ignited my desire to design diving equipment. Many years and 3 engineering degrees later I started work as an engineering consultant at Scubapro.